A PERSONAL ACCOUNT OF AN ECLIPSE EXPEDITION

By David Le

Conte

An account written following an

expedition to see the total eclipse of the Sun on 26 February 1998.

On the flight out to

Venezuela to see the total eclipse, Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau

joined us in a film called Out at Sea,

a story of two old men going on a cruise ship to view a total eclipse of the

Sun. Despite the fact that the film showed a Full Moon on the night before the

eclipse and the night of the eclipse (!), it was an enjoyable comedy, and the

coincidence of an eclipse film on an eclipse trip put us in the right frame of

mind when we landed at Caracas, after a tiring nine-hour flight. A further

domestic flight took us to the oil town of Maracaibo,

right in the path of totality for the eclipse  four

days later.

four

days later.

We met our friends

and hosts, Roger Tuthill and his wife Nancy, at the

hotel, along with a group of some two dozen Americans, including a number of

amateur astronomers intent on viewing what was to be a most spectacular eclipse.

During the two nights and three days after arrival we went high up into the

Andes, staying at a hotel in the small town of La Mesa at an altitude of 7,000

feet, where it was hoped to view the night sky. Unfortunately, this was not to

be, as the conditions were too cloudy on the first night, especially in the

southern part of the sky which we were interested in, being that part which is

not visible from Guernsey. And on the second night it was totally cloudy, so it

dashed our hopes of seeing such wonders as the Large Magellanic

Cloud, the Tarantula Nebula, the Southern Cross, the Jewel Box, and Coalsack, the Eta Carina Nebula,

and other southern sky wonders totally invisible from  Guernsey latitudes.

Guernsey latitudes.

However, in the

intervening day we ascended even higher, well above 13,000 feet, to the Eagle’s

Peak Pass, or the Paso de la Aquilla. Being Carnival

time, and a holiday, this place was crowded, despite its remoteness.

Nevertheless, we were able to find a secluded spot from which one of our party

set up an 80 mm telescope, with which, protected by a Solar Skreen

filter which I provided, we were able to get a beautiful view of the Sun, and

were excited to note that there were two good groups of sunspots, which would

make the ensuing eclipse even more enjoyable.

As indeed it proved

to be, when Thursday, the 26th of February came, after much preparation and

excitement, and our group set off for the 45-minute drive to Fuerta Mara, or Fort Mara. This was an army base, just 20

minutes from the Colombian border, a very sensitive and rather dangerous area.

We were fortunate, therefore, to be well guarded, and in fact had to go through

military procedures in order to gain access to and egress from this army base.

On the way to the base we passed many people preparing for the eclipse,

particularly at the Planetarium Simon Bolivar, where there were to be organised

observations of the eclipse. There was much excitement in the air, as well as

music provided by local guitar bands.

We set up over three hours before the eclipse,

and had plenty of time to check and re-check our equipment. Besides our group

there was a number of other groups, including Germans and Swiss, as well as

Venezuelan and American, all with telescopic and photographic instrumentation.

There was an excited buzz in the air, being accompanied by some music, and an

increasing interest by the soldiers.

We were just about to set up with our cameras,

tripods and binoculars, as well as equipment for testing safe methods for

observing the eclipse, when we were suddenly swamped by crowds of people,

including many children and media representatives, television cameras and

journalists, many of them accompanying the Governor of Zulia

State, who was touring all the major eclipse observation sites. We were pressed

with many questions, as well as being so physically pressed that it was hard to

move from time to time, and we were in danger of having tripods knocked. There

were groups of Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, and other youngsters, and they loved

the eclipse viewers which we gave to them to see the eclipse safely.

The site was a

recreational field used for football and baseball, as well as for army

manoeuvres. Indeed, right next to it was an assault course, including macabre

hanging dummies, which no doubt got bayonetted and

shot at many times during army exercises. In some respects it was a little

unnerving, having military men all around us, some carrying guns, but in other

respects, knowing how close we were to the Colombian border, and the danger

that presented, we were quite fortunate in being well protected by a

sympathetic guard force, led by a Base Commandant who was himself an amateur

astronomer. We were indeed made very welcome, and the local community laid on

refreshments in the form of cooling drinks, which were so necessary on such a

hot day. Temperatures reached as high as 40°C. The Army had also damped down

the field before we arrived; otherwise conditions would have been unbearably

dusty, as there was a slight wind.

As the moment of

first contact was reached there was an increasing buzz of activity, as people

carried out final checks on their equipment, and settled in to watch an eclipse

in the most perfect of conditions.

As the moment of

first contact was reached there was an increasing buzz of activity, as people

carried out final checks on their equipment, and settled in to watch an eclipse

in the most perfect of conditions.

Earlier

in the morning there had been some cloud, but, true to the previous days’

experience, the cloud soon cleared away to give a perfectly blue sky, with the

searing hot Sun beating down on a totally un-shaded area. Fortunately, we were

well prepared, with lashings of sun cream and mosquito repellent, as well as

floppy hats, cool shirts and shorts. Elegance was not the main concern - it was

to be as comfortable as possible on this long-awaited day.

Although this was my

first experience of a total solar eclipse, I have seen many partial eclipses,

and so the initial hour or so of the eclipse was very familiar, as, just after

first contact, one could see through filtered telescopes, binoculars and

telephoto lenses, a tiny niche taken out of the Sun, and growing amazingly

rapidly as one watched. This was, of course, the cold, dark New Moon occulting

the Sun's glowing hot disc.

We had prepared a

sequence of photographic observations, which was carried out with reasonable

faithfulness, despite occasional problems with cameras. This involved taking a

series of exposures to record the progress of the eclipse.

So far, during the

partial phase, this was relatively routine, but as time progressed and the

amount of the Sun’s disk visible became smaller and smaller, the excitement

grew, until a few minutes before the total part of the eclipse the excitement

and emotion was almost unbearable.

We knew from many

previous readings and discussions exactly what was going to happen - or at

least we thought we did. But nothing could prepare us for the few minutes

before and during the total part of the eclipse. About 15 minutes before this

moment the sky grew noticeably darker. The darkening increased rapidly, until

in the last few seconds it descended upon us like a huge dark blanket. The air

grew noticeably cooler. The background voices of the two or three hundred

people present grew louder as people exchanged experiences and emotions. There

was much excitement about five minutes before totality when Venus became

clearly visible. At the same time I noticed that the image of the Sun which I

could see through the camera became much clearer and much more easy to focus,

as the sky background became darker.

The

final minute or 90 seconds of partial eclipse was extraordinary, as so much

happened so quickly. It was impossible to take it all in.

Someone shouted: "Look at the shadow

bands!" We had laid a white towel on the ground, and racing across it were

wavy dark bands of light moving westwards at a rapid rate. These dark bands,

which clearly must be caused by some interference effect, are not wholly

understood, and many people said that the bands on this eclipse were the

clearest that they had ever seen. They were certainly much more evident, much

faster moving, and moving in a different direction than I had expected. Someone

said that they saw two lots of bands crossing each other from different

directions.

Immediately then, all eyes were skyward, filters

removed from cameras and telescopes, as, within just seconds, Baily’s Beads and then a beautiful, brilliant Diamond Ring effect

were visible. This was one of the most extraordinary sights, lasting as it did

just a couple of seconds.

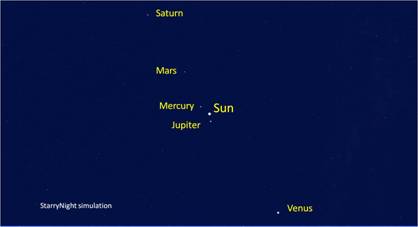

Now we were plunged

into totality, the sky as dark as twilight, and an extraordinary colour,

indescribable, except that the main element of it was

blue, lightening around the horizon, but of a most vivid effect not evident in

any photograph I have ever seen.  Here was the Sun, with its planets, hanging in the sky.

Besides Venus, Jupiter and Mercury were clearly visible, and, for the first time

in my life I saw the Solar System. One could sense the three-dimensional depth

of space, ourselves journeying on planet Earth, accompanied by the Sun as the

centre of our System, surrounded by brillia nt planets. To my surprise, no bright stars were visible,

although Fomalhaut, Altair and Deneb

were indeed in the sky at the time. Experienced eclipse watchers said that this

was a dark eclipse; indeed some of them said that it was the darkest they had

ever seen. Nevertheless, I could not see Mars or Saturn, or any bright stars,

just three planets: Mercury, Venus and Jupiter, in their appointed places in

their orbits, circling around the Sun. This was the Solar System in real life,

as it is impossible to see during any other time than a total eclipse.

Here was the Sun, with its planets, hanging in the sky.

Besides Venus, Jupiter and Mercury were clearly visible, and, for the first time

in my life I saw the Solar System. One could sense the three-dimensional depth

of space, ourselves journeying on planet Earth, accompanied by the Sun as the

centre of our System, surrounded by brillia nt planets. To my surprise, no bright stars were visible,

although Fomalhaut, Altair and Deneb

were indeed in the sky at the time. Experienced eclipse watchers said that this

was a dark eclipse; indeed some of them said that it was the darkest they had

ever seen. Nevertheless, I could not see Mars or Saturn, or any bright stars,

just three planets: Mercury, Venus and Jupiter, in their appointed places in

their orbits, circling around the Sun. This was the Solar System in real life,

as it is impossible to see during any other time than a total eclipse.

But let me return to the Sun itself. The first most

noticeable thing about the totally eclipsed Sun was the wonderful Corona. We

were not yet at sunspot maximum, although there were sunspots on the disc of

the Sun. So the structure of the Corona was perhaps at its most interesting,

filaments streaming out from the equatorial regions, with beautiful spikes

sticking up from its north and south magnetic poles.

But let me return to the Sun itself. The first most

noticeable thing about the totally eclipsed Sun was the wonderful Corona. We

were not yet at sunspot maximum, although there were sunspots on the disc of

the Sun. So the structure of the Corona was perhaps at its most interesting,

filaments streaming out from the equatorial regions, with beautiful spikes

sticking up from its north and south magnetic poles.

To add to the spectacle, prominences were

clearly visible on the limb of the Sun, being first uncovered and then covered

up as the Moon progressed in its orbit.

I was rapidly taking photographs for all I was

worth, trying occasionally to get a good view of what was happening around me.

The emotion and excitement were indescribable. My son Christopher was calling

out exposures and running a video camera. Maureen was describing the scene, and

looking through binoculars at the Sun. Everyone at the moment of totality cried

out with delight. Looking through the camera, fitted with its 1000 mm telephoto

lens, I was clearly able to see every detail of the Sun. I was determined to

get photographs if at all possible. Despite all my preparations and planning

for photographic sequences, it was impossible to stick to it, and I just shot

away at as many different exposures I could think of, changing lenses in the

middle to a 500 mm lens in order to get the outer Corona with longer exposures.

Although I had

planned for this event for a year, had read everything I could on the subject,

had spoken to many, many people who were experienced eclipse watchers, nothing

had prepared me for this experience! A treat, but oh, what a short treat, and

so soon over. I was astonished when Christopher said that there was just one

minute to go before the end of totality. This eclipse was 3 minutes 45 seconds

long - more than twice as long as the 1999 eclipse - but it seemed to flash by

in seconds. It was both the longest 4 minutes and the shortest in my lifetime.

It was long because so much was happening, and there was so much to take in,

that I have never had such a visual and emotional experience crammed into just

four short minutes. And it was short because it was so soon over. The Diamond

Ring reappeared, Baily’s Beads reappeared, the

crescent of the Sun reappeared, and suddenly a light was switched on over the

whole area as the Sun‘s rays once more touched the Earth.

Extraordinarily, and

again despite all our preparations, we had no idea what to do next. What we had

seen had been so overwhelming that it seemed that our whole life, let alone the

next few minutes, would never be normal. We knew that millions of people in

Venezuela were sharing that experience, and that in a number of Caribbean

islands that experience and those emotions were being repeated time and time

again over the next 20 or 30 minutes.

We were eventually

able to pull ourselves together and return to our photographic programme, to

conduct experiments on pinhole projection and mirror projection, to take

photographs of crescents formed under trees by the pinhole effect of the gaps

between the  leaves, and take photographic evidence of shadow

sharpening. Gradually life returned to a semblance of normality, but all of us

exchanged our feelings about the experience, and tried to describe, ineffectively,

what we had seen.

leaves, and take photographic evidence of shadow

sharpening. Gradually life returned to a semblance of normality, but all of us

exchanged our feelings about the experience, and tried to describe, ineffectively,

what we had seen.

We had set up a

thermometer in the shade, in order to measure air temperature changes during

the progress of the eclipse, and the accompanying diagram shows the remarkable

temperature variations.

Gradually, the

equipment was dismantled and loaded onto the bus. We paid a visit to the

delightfully supportive Base Commandant, and made our way out of the Base. At

the exit we were stopped by the guards, and two stern-looking soldiers with

machine guns came on board, and walked menacingly up and down the aisle,

inspecting our group. Eventually, smiles were exchanged, and we were waved on

our way.

What a delight it was

to relax in the hotel pool later in the afternoon, enjoying a drink and

discussing how our pictures might turn out, what we had done right and what we

had done wrong.

I shall remember that

day for the rest of my life. I was particularly pleased to see the young people

enjoy the whole experience. They were fascinated by the pinhole projection;

they were delighted by the eclipse, and after it they sang and danced. What a

wonderful experience for such youngsters. I wish that I had had such an

experience early in my life.

I was just their age

when I first read about the 1999 eclipse, and thought, all those decades ago,

how exciting it would be when eclipse day finally comes. Well, it has come to

us at last - the first total solar eclipse in the Channel Islands for over a

thousand years. How fortunate we all are.

The picture shows Maureen, Chris and David just after

totality. The dark area on Chris’s shirt

is not sweat – it is the sharp shadow caused by the light

from the Sun’s narrow crescent. Picture

by Nancy Tuthill.

As I am now dictating

these memories, I am on the 'plane returning to Europe. Sitting on the right

side, I have a view of the southern sky from an altitude of 37,000 feet, much

higher than that which we reached in the Andes. The sky is brilliant with

bright stars. The Southern Cross is visible at a good altitude. Stars which I

have never seen before are hanging there in space. I am flying above an Earth

which itself is speeding through space, and, despite my theoretical

understanding of our position in the universe, it is all so much more visually

clear now that I have had the experience of a total solar eclipse. It is as if

I am in a space-ship, circling round the Sun, keeping within the shadow of the

Earth, as it is a dark, dark night. If I were really out in space I would not

need an eclipse to be able to see the day-time planets, as there would, in

effect, be no day-time or night-time; just a perpetual star-studded sky. I

cannot believe the eclipse has ended, as it re-runs and re-runs through my

mind. I want to repeat the experience, but I know that each eclipse experience

is different, and that the first cannot, in any case, ever be repeated. I am

just so thankful that my first eclipse was such a spectacular one, and in such

perfect conditions, and that I could share it with such a wonderful group of

people. No, life will never be the same, and how relatively empty my life would

have been without such an experience. On the 11th August 1999 millions of

people have the chance of being in the path of totality, so that they too can

experience this once-in-a-millenium phenomenon.

© David Le Conte, February 1998 (amended slightly in December 2010)

Quotations about

eclipses – A selection of quotations from literary and

historical sources.